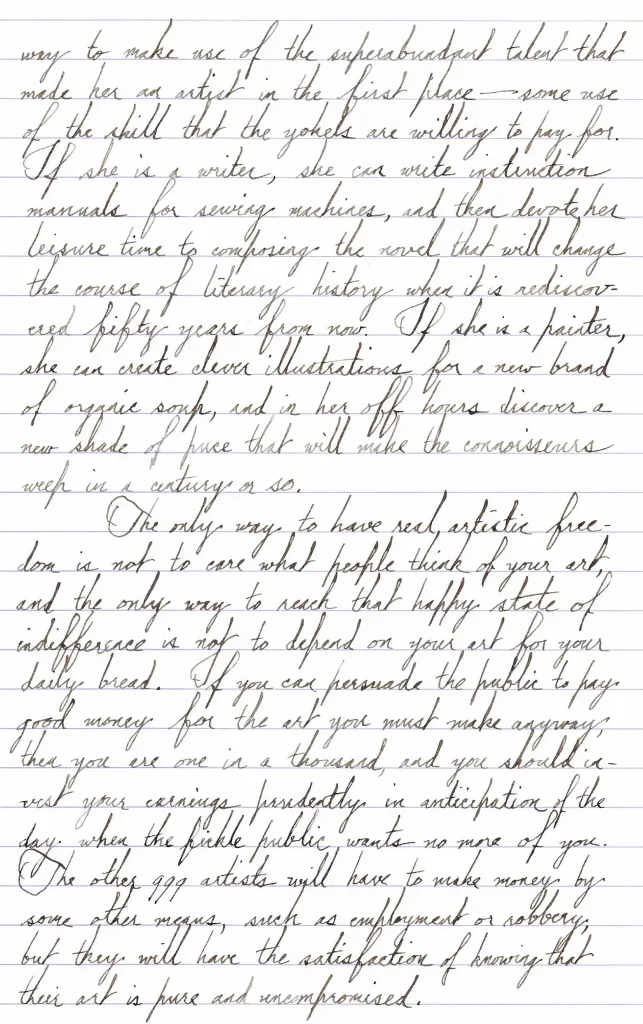

Transcribed below. The pen is an Esterbrook No. 048 Falcon with Walnut Drawing Ink.

Artistic Freedom

or, Who Needs an Audience?

We hear quite a bit of grumbling about artistic freedom from artists who think they don’t get enough of it. To some extent, they have a right to grumble. If anyone tries to tell them that they may not produce their art, they can object, and they ought to object.

There are limits to even this kind of freedom. If an artist declares that she belongs to the Detonationist school, and her art is blowing up people’s houses, then we who live in houses have the right to tell her she is not allowed to do that, and even to call the police if she seems about to attempt it. But art that causes no physical harm must be allowed, no matter how vile we think it is.

Often, however, the artist who demands artistic freedom is not one who has been prevented from making art. The art has been made, and now the artist is demanding that somebody pay for it. Here the artist has run up against the ugly fact that other people have artistic freedom, too. The artist has the freedom to make all the art she likes, and we have the freedom not to like it. Artistic freedom belongs to everybody, inconvenient as that may be to the artists.

It is very distressing to artists to discover that the public does not like their art. It may have little to do with the quality of the art. Edward Bulwer-Lytton wittered on about his work as a Poet in a way that made every real poet want to murder him, but millions of readers bought his books. Herman Melville wrote one of the greatest novels in the English language, and it destroyed his career. In the world of art, justice is usually delayed, and too frequently never comes at all. This is the price we pay for artistic freedom.

What can the artist do? The public don’t know good art when they see it. Give them a choice between your masterpiece and formulaic rubbish, and they will puck rubbish every time. It’s enough to make a real artist despair.

But what can the artist do when it’s obvious that the yokels won’t pay for Art with a capital A? Well, it can be satisfying to rant. This is why artists form movements and then secede from them and form other movements. They are looking for a compatible group of other artists who will listen with sympathy to all their complaints about those Philistines who don’t really understand art. As soon as a certain number of members of the movement say, “But I don’t understand that stuff you’ve been doing lately either,” it’s time for a secession.

These movements are to be encouraged, because they give starving artists something to do while they starve. But they are more suited to the artists who enjoy talking about art more than making art. Those artists are probably in the majority. The minority, however, want their artistic freedom so that they can make the art that is burning a hole in their souls trying to get out.

We need not tell those artists that they should go ahead and create their art. They will, because they must. For them, the question of artistic freedom comes up once they have made the art and discover that the yokels want Thomas Kinkade instead.

The most practical and satisfying response to that discovery is cynicism. Of course the great herd of Philistines don’t know art when they see it. Who expected anything better from them?

The properly cynical artist has all the artistic freedom she could desire, because the question of whether anyone will pay for the art has been removed from consideration. This does, however, necessarily imply that she is not making money from her art. But most artists are not making money from their art. The cynic is the one who is psychologically prepared for what seems to hit the others as an unexpected slap in the face. A grim view of the human species gives her a sunnier outlook on life.

In an ideal world for artists—painters, writers, theremin-players, poets, dancers, poodle-groomers, and so on—the creation of art would be financially rewarded according to the artist’s own estimate of the merit of the work. But the rest of us could not afford to live in that ideal world. In the world we have actually built for ourselves, artists are reduced to the same necessity that plagues every other trade: they must persuade people with money to hand over some of that money in exchange for their skill and labor. Here they find themselves at a disadvantage against some of the other trades: the average Philistine perceives the value of an unclogged toilet more easily than the value of an abstract sculpture. This is why many artists rely on a more apparently useful trade for their income. It may also be why so many of the artists who do make a living from their art seem to be second-raters: they have put more effort into learning to extract money from its lurking-places than they have put into producing art.

The best plan for the artist who wants to produce art without compromising her artistic vision is to be independently wealthy, preferably through inheritance. But this avenue is not open to every artist. The next-best thing would be to find some way to make use of the superabundant talent that made her an artist in the first place—some use of the skill that the yokels are willing to pay for. If she is a writer, she can write instruction manuals for sewing machines, and then devote her leisure time to composing the novel that will change the course of literary history when it is rediscovered fifty years from now. If she is a painter, she can create clever illustrations for a new brand of organic soup, and in her off hours discover a new shade of puce that will make the connoisseurs weep in a century or so.

The only way to have real artistic freedom is not to care what people think of your art, and the only way to reach that happy state of indifference is not to depend on your art for your daily bread. If you can persuade the public to pay good money for the art you must make anyway, then you are one in a thousand, and you should invest your earnings prudently in anticipation of the day when the fickle public wants no more of you. The other 999 artists will have to make money by some other means, but they will have the satisfaction of knowing that their art is pure and uncompromised.

Leave a Reply